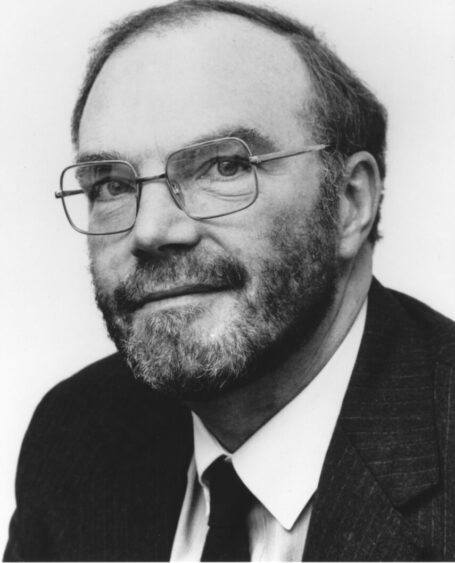

Celebrating 1984 Templeton Prize Laureate Michael Bourdeaux

By Juliette Plummer

In 1973, the first Templeton Prize was given to Mother Teresa. In 2023, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of this award. Over the next 52 weeks, we will highlight each of our laureates and reflect on their impact on the world. From humanitarians and saints to philosophers, theoretical physicists, and one king, the Templeton Prize has honored extraordinary people. Together, they have pushed the boundaries of our understanding of the deepest questions of the universe and humankind’s place and purpose within it, making this (we humbly think) the world’s most interesting prize.

Michael Bourdeaux was born in March 1934 to a baker and a schoolteacher in Praze, Cornwall, England. He spent a year at Moscow University in 1959, as part of the British Council’s first wave of exchange students to the Soviet Union. Bourdeaux’s trip in Moscow happened to coincide with the start of a particularly intense wave of Soviet religious persecution.

After finishing his studies in the Soviet Union, Bourdeaux studied theology at Oxford and was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1960. During a trip to Moscow in 1964, he met with a group of Russian Orthodox believers who begged him to “be our voice” and warn the world about religious persecution in the Soviet Union.

He established the Centre for the Study of Religion and Communism in Kent, England, in 1969, which later became Keston College. Bourdeaux attempted to marry impartial scientific research on the current state of religion in communist nations with genuine support for religious freedom. The college is now known as the Keston Institute, and it has grown into one of the leading sources of information on religious freedom in Communist and previously Communist nations.

Bourdeaux was awarded the Templeton Prize in 1984 for his efforts to investigate and explain the deliberate annihilation of religion in Iron Curtain countries during the Cold War, as well as to protect the rights of citizens in these countries to worship as they saw fit. When the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc fell, Bourdeaux’s efforts for worldwide religious freedom were widely appreciated. On May 15, 1984, Bourdeaux received the Templeton Prize medal from Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, at a private ceremony at London’s historic Guildhall.

We look back on some of the remarks delivered at the Templeton Prize ceremony in 1984 by Michael Bourdeaux, Edward du Cann, and Sir John Templeton.

The Christian Church was born in suffering and persecution. Christ died the death of a criminal. Rome oppressed Israel. For three centuries the Early Church faced physical extinction almost daily. Yet it’s probably true that more Christians have suffered for their faith in this century than in any other in history. At the same time in a world of compassion for many causes, those who do not suffer for their faith find it very difficult to stand beside those who do. In America many churches have a suite of offices, usually with plush carpets and computer records. In the Soviet Union thousands of towns and villages are permitted no church at all and even a duplicating machine is illegal for a believer. Yet in God’s amazing providence it’s the second which has more lessons of faith to teach the first than vice versa. The world is still blind to this, but reading the Bible should have led us to expect it long ago.

Many faces bear the marks of suffering, but on every single one that suffering is turned to joy: the joy is the certain knowledge of the resurrected and living Christ, a lesson of life and experience, not of Christian books, which are virtually unobtainable anyway. Neither did the Apostles learn of the Resurrection from books. Not in our theological colleges, not in our synods, no, not even in our evangelical campaigns do we find such certainty. We may preach the Gospel: they live it. All our machinery and organisations are ultimately dispensable: the Body of Christ is not. The Russian Christian knows he’s joined in that Body by the great and noble army of recent martyrs, tens of thousands from the ’twenties and ’thirties — and yes, some from the ’eighties, too. We’ve lost our nerve in affluence; they’ve discovered it in persecution.

Michael Bordeaux

Those who keep their faith alive in circumstances of difficulty or severe personal risk desperately need our prayers. Michael Bourdeaux, I feel, is a practical answer to them. His message is that those who suffer for their faith are not forgotten and they will not be forgotten. The award of this Templeton Prize to him is a further answer to our prayers. As a result, Michael Bourdeaux’s work is now more widely known than it ever has been. We must all hope and pray that the result of the advertisement of his devotion will be increasing public support for the painstaking work carried out at Keston College.

Edward du Caan

God is beginning to create His Universe. How grateful we should be that he permits each of us to participate in some small way in his divine on-going creative process. God is revealing Himself more and more to the astronomers, physicists and geneticists. God is now revealing His creative processes of overwhelming beauty. By vast research in a single century scientists have multiplied our knowledge of God’s creations more than a thousand fold. His creative methods are awesome and beautiful beyond anything man previously imagined. Each revelation gives us new knowledge and new mysteries. By studying His creations we learn about the creator. We increase not only our understanding but also our love and gratitude to our divine creator. The majesty of His creations commands our awe and the depth of our worship and overwhelming thanksgiving for His millions of blessings and miracles.

John M. Templeton

Still Curious?

Learn more about 1984 Templeton Prize laureate, Michael Bourdeaux here.